My Writer’s Voice Linked to A Childhood Spent in the NSW Clarence Valley

The following historical photograph of my hometown, with the Clarence River and Susan Island across the water, bring me back to long-forgotten memories of childhood evenings underneath a balmy star-spangled sky in South Grafton next to the water’s edge. I wonder now whether this is the source of my writer’s voice: the places and storytellers from childhood that I carry within till this day? And for me, nature played—and still plays—a large part.

Grafton on the Clarence. State Archives NSW

Is it the past that gives birth to the special voice within all of us, the one that reappears when narrating stories in written form? This throws up other questions for me, to do with the the relationship of voice to person, character and narration, and how “written voice” touches vicariously on an assumed reader and an assumed listener.

We were an unruly composite of uncles, aunts, siblings and neighbours, as a dark-skinned man that we kids knew as “Uncle Sammy” kept us spell-bound with tales from the Arabian Nights. His deep voice wove magic on us, retouching millenia-old yarns with an Aussie flavour that pulled us into the caves of Ancient Syria, whilst sitting on manicured lawn on the banks of the Clarence River in Grafton.

Clarence River-way upstream: Adam Gordon, Flickr 2012

Other story-tellers from childhood were on the Irish side of my family: my mother and her mother, Grandma Walker; the Walker uncles, especially Uncle Bargy (pronounced /bah-ghee/), who was a stutterer. When Bargy told a story, his stutter magically disappeared during the telling of the tale.

And of course there were my teachers, many of whom were experts or naturals when it came to telling a good story. I remember the fairy stories that filled me with dread or longing in kindergarten, “Hansel and Gretel” and “Cinderella”, and later on, the stories of explorers, such as Burke and Wills, who perished in the desert. Then there was the teacher who recited “The Forsaken Merman”, reducing me to tears for the family of mer people abandoned forever by the human wife and mother.

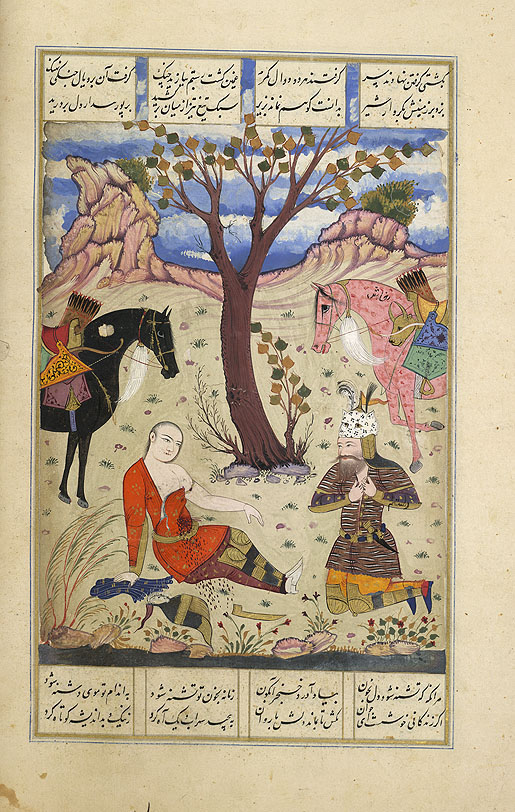

Sohrab and Rustum

And then, in Year Nine in high school, there was an occasion when I was reduced to a weeping mess as the teacher read out a long narrative poem, “Sohrab and Rustum“, by Matthew Arnold, about a father and son on opposite sides in battle, the father killing the son, who dies in his arms on the battlefield.

And so I realise now that it is to these story-tellers, the flesh-and-blood ones, that I owe a debt of gratitude for opening me up to the power of narrative. With a short story, it is important to know who is telling the story—the narrator behind the words— in mastering the concept of voice. Within a novel it can be more complex, as several “voices” might be used in retelling. However, many agree that each author has a particular “voice”, which distinguishes her from others.

Voice and person are closely connected. The choice of a certain person—first versus third—will greatly affect voice, just as the choice of a certain character will assume a certain voice distinct from other characters in the story. This is what writers mean, when they say that the characters took over and pulled the narrative along. I believe the voice we choose when we write creatively is linked to the stories—the voices—we heard when we were little. And to the smells, sounds, images and feelings arising from the environment we found ourselves in.

My sense memories will forever be imbibed with the minty fragrance from eucalyptus trees and stories on the riverbank.

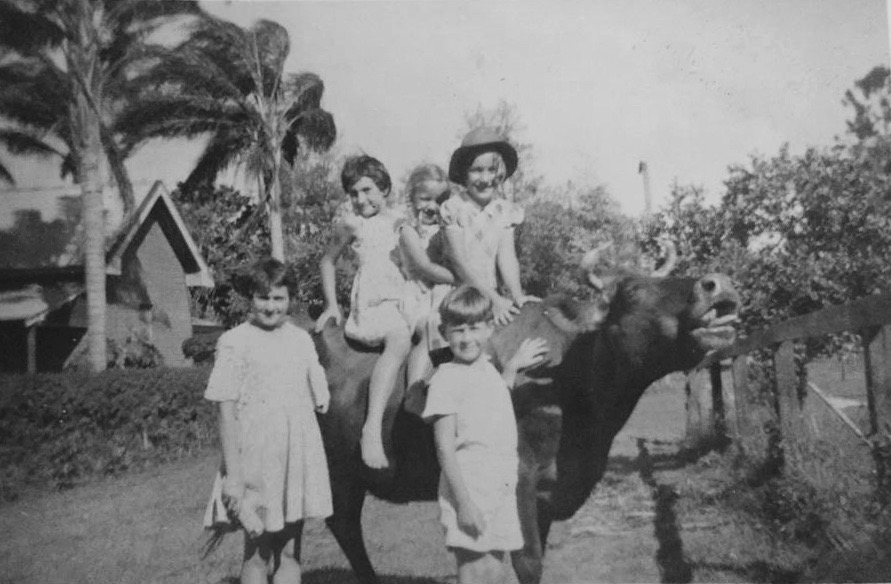

Riding a cow at the Howleys

I find your posts to always be interesting and this one is especially so. Voice: I accept the concept, but don’t really understand it fully. I experience and recognise the differences in voice from my favourite authors, but am certain I have not developed a voice of my own in my writing. Like you I was blessed with good story tellers and good oral readers of stories as a child, both at home and at school. Stories and poems, free verse or tied format I lapped them up; “The Highwayman”, “Sohrab and Rustum”, the narrative poem with strong tragic themes by Matthew Arnold, “The Forsaken Merman”, Sir Walter Scott’s “Lochinvar” and many more. In my teens limericks were a joy, sonnets interesting and Haiku a real eye-opener. Early and constant exposure to literature like this made me what I am I reckon.

Keep up the blogging, I for one enjoy it (even if all at sea technically.).

So glad you liked this, Ian. My voice when I write well seems connected somehow to the child within. Perhaps it was “Sohrab and Rustum” that I’ve been trying to drag up out of the unconscious sea (or swamp!)for a while now. Thanks for reminding me of the title and the author; it was so sad that I must have blotted it out. Does one brother mortally wound the other in battle, and he’s holding him in his arms as the blood flows out and he expires? Or were they just friends? I must look it up again.

Sohrab and Rustum were father and son. At the end of the free verse poem the son killed the father in a one-on-one champions battle. I cried, but being in my mid teens in an all boys school had to hide the emotion as best I could.

I will definitely read it again. Was it in Year 9?

Thanks Ian

Me too, I’ll re-read it and see if my reactions have changed at all.

Anne, as usual I got it wrong, but nearly right … the father killed the son (I found the poem, skipped to the end to check my memories).

Read the poem at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poems/detail/43604

I am about to start from the beginning … soon as I find the tissues.

Great. Thanks. I’ll get back to you about this.

Year nine? Yes that’d be about right, Third Year High School back then and I’d have been 14 going on 15.

Anne, did you ever get to re-read this poem? I have read it more than once over the last six months and “enjoyed” it nearly as much now as I did then (aged 14 or 15).

As a teenager I revelled in sad (poignant) stories, particularly sad poetry. Probably I craved the pathos as I explored and exploited my raging hormones and tried to understand the cycle of birth, life and death (two of my grandparents died when I was in my ‘tweens and early teens). I read so I’d remember not to be too judgmental. I read for perspective and to be reminded that that even in the face of loss and pain, of doubt and confusion, life does not stop.

I re-read now out of reminiscence and in wonder of the younger me. How intense we were then.

Hi Ian

I re-read parts of it, the parts I remembered crying over in class. I felt like I was the only one reacting like this at the time. Another one was “The Forsaken Merman” by Matthew Arnold: “She sigh’d, she look’d up through the clear green sea;. She said: “I must go, to my kinsfolk pray, In the little grey church on the shore to-day. ‘T will be Easter-time …” So sad! You were always wise for your age, by the sound of things. You feel so much better after a good cry, as long as no-one is laughing at you while you do it! Big kids don’t cry etc etc…