THE NIB AWARD

THE NIB AWARD

The Waverley Library Award for Literature, established in 2002, is entitled ‘the Nib’. Organised and financed by Waverley Council, it is managed by Waverley Library, with the support of a committee, and a number of community establishments, including Friends of Waverley Library, Gertrude & Alice Bookshop, and local RSL Clubs. The Nib promotes research-based Australian literature, with a generous prize of $20,000.

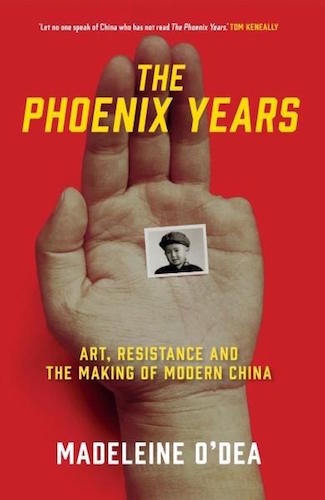

Definitely the best book I have read this year, is one of the finalists for the 2017 Nib Award. It’s The Phoenix Years : Art, Resistance and the Making of Modern China by Madeleine O’Dea. Foreign correspondent Madeleine O’Dea has been an eyewitness for over thirty years to the economic success of China, the ongoing struggle for human rights and free expression there, and the rise of its contemporary art and cultural scene. Her book, The Phoenix Years is vital reading for anyone interested in China today.

Tom Keneally, author of Australians sums it up nicely: ‘Amidst all the chatter about China lies this rock of a book, a magnificent memoir/ history from the very core of modern Chinese society and history. … Let no one speak of China who has not read ‘The Phoenix Years’.

THE BOOK

This book piqued my interest as a long-term second language teacher with adult migrants (AMES) and the Institute of Languages (UNSW). The book relates the heady years of hope and creativity in the 1980s, which ended in the tragedy of the Tiananmen Square massacre. Following that disaster, government members in China turned their backs, once more, on the people, while feathering their own nests and ruthlessly promoting economic success above all else. Human rights and the environment were disregarded in favour of economic advancement at all costs.

Among those who would not be silenced, was a particularly poignant group, the now middle-aged ‘Tiananmen Mothers’ who continued to keep alive the memory of their sons and daughters, whose lives were brutally cut short by the massacres on June 4th 1989.

I was left, after reading the book, with a terrible sadness at the fate of the freedom fighters in China, and with an anger against the government cadre, who were prepared to shed the blood of their own citizens for greedy self interest.

Was the price of modernisation—China’s economic boom and thriving metropolises of today—worth the loss of lives, the resulting traumatised nation and a denuded countryside? I think not.

At the same time, I was left with an overwhelming admiration for the people of China, for the students, the artists and the ordinary citizens who supported them in their battle against the authoritarian regime. It reminded me a little of the year of 1968 that I spent in Paris during the student/workers’ strike, when ordinary citizens passed water and food down from their balconies to help the students in their battles with the government of General de Gaulle.

One of the lasting images for me is of the young female artist Pei Li’s work depicting in a darkened box a video of a girl : ‘From time to time she would pick up a can and spray-paint on asking “Isn’t something missing?” over and over again. The work was exhilaratingly angry and exhausting, with its cycle of creation and destruction played out to a screeching soundtrack.’ (Chapter 9).

If you don’t get to read any other book this year, I recommend this one, published by Allen&Unwin 2016, to you.